When I was a kid, four food groups competed in our house. Each group viewed the others with suspicion and claimed itself superior. My two grandmothers, and my mother, each stood like a pillar for a variant of Chinese food. My grandfather was an outpost of English food.

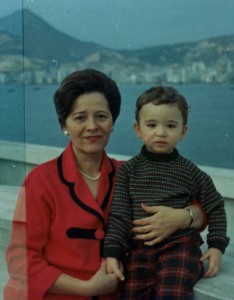

My paternal grandmother, Annie Chan, was all about comfort food. Here she is in 1965 with my brother, overlooking Hong Kong harbor. Her standby was si yao gai (soy sauce chicken), and when I took the title of world’s pickiest eater she suggested things like haam sin choi (salt cured napa cabbage) and haam yu (salt cured fish). Haam yu in particular made me run screaming. It exudes a continuous explosion of preserved fish smell. Now of course, I like it. What I never understood is why suggest haam yu to a kid who almost barfs at the sulphur smell of boiled egg yolk. But it made sense to her. And she had spent some time being hungry, when these kinds of inexpensive preserved foods kept people alive. Haam sin choi was very friendly to me, like salty candy.

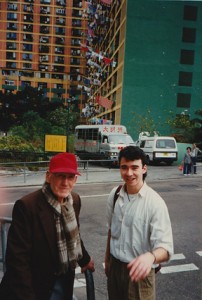

My grandfather, Ernest Sayer, had lived most of his adult life in Asia but proper food was English food. Here he is in front of his apartment building, with my brother, sometime in the 80s. He and my grandmother had separated before I was born. When he came to visit, the big anticipated treat, which my father would often cook, would be English breakfast: bacon, fried eggs, fried tomatoes, and fried bread. I was not a good grandchild. After eating this I’d lie on the couch for hours with a stomach ache. I now realize it was from the cloud of greenhouse gases that bloomed in my intestines after processing so much oil, and I wasn’t used to it. Because of this I was intimate with other venerated English products: Woodward’s Gripe Water, and Activated Charcoal tablets. As far as I was concerned, the English deserved the world gold medal for boiling sugar. I was perfectly willing to live on barley sugar, Allen & Hanbury’s Blackcurrant pastilles, butterscotch, licorice toffee, and a whole rainbow of fruit-flavored lozenges. Oh, and Ribena. I gave myself a lot of cavities.

Here is my maternal grandmother, Chen Mun Fong, dressed up for a wedding. She grew up in an educated Chinese household and comfort food was never something she’d turn to if she had other options. On the contrary, she upheld legends of fantastic foods, such as private groves of miraculously sweet oranges that were slashed by communist revolutionaries, never to be seen again. A preserved egg was not something you shoveled into your mouth with rice. What you do is get a few high quality preserved eggs, and slice and serve them drizzled with special aged vinegar and thin slices of pickled ginger. Young ginger, mind you.

The fourth food group, and really the invincible one, came from my mother. Hers was both a derivative of and a rebellion against the model of her mother, Chen Mun Fong. She took full advantage of the Hong Kong melting pot. Pinnacle of all food: a steamed fish (one that had been swimming a few minutes before cooking). But she liked the high and the low, the east and the west: won ton mien (from a dai pai dong–street vendor), crepes with orange butter, beet borsht–as long as it was fresh and tasty. And one must don napkins and sit down to gorge when mangoes and papayas are ripe. Again, I was an unfilial child, as I didn’t like any of it. There was no concept of kid-friendly food back then, and my mother would have been horrified at the idea of raising a child on Captain Crunch and chicken nuggets. Dead, boxed food, no way.

I call my mother’s food group invincible because it had the most influence on me, in the end. Depending only on time, things could have gone one of four ways.

Comments

One response to “The Four Food Groups”

that was really funny – there was Woodward’s gripe water in my childhood too, usually administered to colicky infants.